From Evernote: |

Nicaragua’s New Day : Condé Nast TravelerClipped from: http://www.cntraveler.com/features/2011/09/Nicaragua-s-New-Day |

Nicaragua’s New Day

From the volcanoes of Granada to the surfer paradise of San Juan del Sur, Andrew Cockburn explores the pleasures and paradoxes of Nicaragua.

Thirty-two years after the revolution that rocked this hemisphere—and on the eve of a fraught election (Daniel Ortega, again?)—Andrew Cockburn savors Nicaragua’s natural charms and political paradoxes (and does some fine fishing, too).

Time runs differently in Nicaragua, as became obvious during my final approach into Managua‘s Augusto C. Sandino International Airport. Though it was late April, brightly colored Christmas lights glowed around the city, with one particularly impressive display close to the shore of Lake Managua visible from miles away. On the ground, people complained about the heat but confidently predicted the imminent onset of invierno—winter—which would bring rain.

The past intrudes on the present here in a variety of ways. Most city streets, for example, have no names or numbers. Managuans give their addresses in reference to places that often no longer exist. Many vanished landmarks come up in conversation this way: “two hundred meters behind where the Pepsi plant used to be” or, most charmingly, “next to where the little tree used to be.” The convention dates back to Managua’s near-total destruction in the December 1972 earthquake. Familiar surroundings obliterated, the survivors could designate locations only by what had been. Re-creating their city, they moved away from the lethally unstable historic downtown and sensibly eschewed high-rises. The result is a sprawl of neighborhoods spreading south from the lake toward the mountains under a canopy of green treetops, as if the city were infiltrating a forest.

Dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle lost his palace to the earthquake, but he recovered quickly enough to loot much of the international aid flowing into the devastated country, thereby confirming the belief among Nicaraguans that his viciously corrupt regime had become intolerable. The hill on which the palace once perched is now part of the Loma de Tiscapa Historical National Park, and after settling into my hotel, I made my way there for its stunning city views—north to what was, pre-earthquake, its commercial heart, and south over a pretty little crater lake and much of what is now greater Managua.

At the summit I found a giant black statue of Augusto C. Sandino, the early-twentieth-century leader of guerrilla resistance to American occupation, who was treacherously murdered by Somoza’s father. Given that Sandino was the inspiration and namesake of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), the ruling revolutionary party that drove Somoza from power in 1979, I would have thought the statue would be the most visible object in the neighborhood. Interestingly, it is not. A few yards away towers a significantly taller, four-sided billboard promoting the candidacy of President Daniel Ortega for reelection this coming November. One side exhorts, “Viva la Revolución!“—exactly the sort of talk that led Washington to launch a bloody secret war against the Sandinistas in the 1980s—but the effect is belied by a large pink heart, reminiscent of a valentine, featured alongside. Another side promotes Ortega’s campaign slogan: “Christian, Socialist, and in Solidarity.” Clearly we’ve come a long way since President Ronald Reagan evoked the specter of leftist Sandinista invaders heading for Harlingen, Texas.

Much of the text on these and other posters is done, I’m later told, in the handwriting of First Lady Rosario Murillo, who combines a powerful grip on the levers of power with an affection for the symbols of the 1960s. The ubiquitous billboards followed me as I left the park and moved east, away from the old downtown to the current “Metrocentro.” Outside the headquarters of the electoral commission I found demonstrators from the Peace, Love, and Life festival. In another time and place, these activists would have been protesting the commission’s clearing Ortega to run for a constitutionally prohibited second consecutive term—Woodstock-generation idealism at its best. But they were state-sponsored Juventud Sandinista (Sandinista Youth), drafted by the ruling party to smother a gathering by Ortega’s critics. Gioconda Belli—Nicaragua’s great poet, herself a veteran revolutionary—remembers Murillo, in a bygone age, sporting hippie tunics and surrounded by rock posters and beanbag chairs. Her old comrade’s evocation of sixties tropes in the service of twenty-first-century state control, she remarked bitterly, is a “manipulation of time.”

Even though at the time of my visit the presidential election itself was some months away, a lot of people were lining up at the electoral commission office. “The official price for a voting card is three hundred cordobas,” explained Camilo Belli, Gioconda’s son and my insightful tutor in local political geography. “But FSLN members get theirs for free.” Belli, a formidable investigative journalist now active in opposition politics, has hopes that voters are keeping the story of El Güegüense in mind. This refers to Nicaragua’s most famous satirical drama, a sixteenthcentury comedy penned by an unknown author, in which a crafty Indian—El Güegüense by name—deceives and outwits the Spanish colonial overlord. In Camilo’s view, accepting a voting card on false pretenses so as to be able to vote as one pleases would be in keeping with tradition.

One well-informed veteran of local politics described the modus operandi of state control as “Somoza lite.” It must be said that the devious stratagems of the incumbents are still a long way from the Somozas’ practices or, for that matter, the intensifying repression currently being waged, amid international indifference, by the military-backed Honduran regime. Even so, vocal opposition to the ruling family’s remorseless accumulation of political and economic power tends to provoke an unpleasant reaction, such as the immediate and financially suffocating attention of the tax authorities.

Outside politics, however—despite grumbles regarding petty corruption—people do not live in fear.”There’s a spot near Masaya”—a town roughly halfway between Managua and Granada renowned for its fiestas and its artisans—”where the cops like to stop foreigners driving fancy cars and shake them down for a few dollars,” a hotel manager told me. “Of course,” he added, “if they knew better, they just wouldn’t stop.” (In Guatemala, by contrast, such insouciance toward law enforcement could be very dangerous indeed.) Thanks to this lack of alienation between police and public—a legacy of the revolution, when the force was formed—the country enjoys a well-deserved reputation for safety, notwithstanding its status as the second-poorest country in the hemisphere, after Haiti.

Nicaraguans naturally take it for granted that peace festivals and other ruling-party outreach initiatives are financed by the reported $500 million donated to Ortega annually (in the form of oil on long-term credit) by Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. The lion’s share of the money, by all accounts, is expended in the political interests of the current ruler, whether in the form of tin roofs for the poor—”very nice if you didn’t have a roof before,” as one Ortega supporter remarked to me—or a bus service in some remote district, or straightforward subventions to party loyalists. A significant portion also seems to go to public entertainment. At a busy intersection not far from the peace and love gathering, we came across preparations for another Ortega-sponsored event. With traffic diverted, workers were assembling bleachers for a live broadcast on giant screens of an upcoming and eagerly anticipated football match between Barcelona and Real Madrid. A sign announced that admission would be free for Juventud Sandinista.

Public festivities are always popular in Nicaragua, as the Catholic Church has long been aware. The distance between Managua and Granada, Nicaragua’s second-most important city and a Spanish colonial town founded in the sixteenth century, is just over an hour by car. On a Sunday morning, after a couple of days in the capital, I drove through Masaya and dawdled in the string of “white towns”—so called for their construction from chalky-white volcanic rock—in the cool hills between the two cities. In San Marcos, I came across an elaborately costumed statue of Saint James being carried aloft, flanked by two other saints and preceded by drummers and dancers in the role of what a local told me were “white Spanish devils.” The procession seemed to be for no one’s benefit but the townspeople marching cheerfully along behind. “We are taking the saint home,” explained one, as if performing a favor for a friend.

The pleasure I take in religious rituals was marred, however, by a more bombastic affair in Granada’s otherwise entrancing Parque Central later that day. Gazing appreciatively from my hotel room balcony at the relaxed throng strolling amid the trees while the beautiful cathedral facing me glowed in the lateafternoon light, I suddenly heard the ominously amplified sound of someone test-tapping a mike. This being one of the most devoutly Catholic cities in Nicaragua, the noise was prelude to an all-night celebration of the late Pope John Paul II’s beatification, complete with jaunty Christian-pop numbers relayed at maximum volume and accompanied by even more deafening blasts from a limitless supply of cherry bombs.

“Granada was the only city that didn’t rise against Somoza during the revolution,” remarked my friend Arturo Cruz as we set out on a nighttime tour. “That’s why most of it is still here.” I could have had no better guide to the venerable colonial capital than this erudite scion of the local aristocracy who tirelessly led me up and down a grid of streets lined with colorwashed mansions and lively with passersby. In the 1950s, he explained, “social status was precisely determined by how close you lived to the Parque Central. Once, I could have bought a house four blocks away for forty thousand dollars, but my mother said it was too far out—’no one lives there.’ ” The smart set worshipped at the beautiful church of La Merced, with its tower that served as the meeting place of Granada’s famous Vanguardia poets, in the twenties and thirties—dedicated, as declared in their manifesto, to “artistic expressions, intellectual scandal, and aggressive criticism.”

Continued (page 2 of 3)

Today, most of the mansions are owned by wealthy foreigners or have been turned into congenial bars, restaurants, or hotels, but for Arturo they are populated with childhood memories and family legends. On a street where he once saw a naked man running from an angry husband, he recalled one house as having contained “dangerous types who might grab an unwary little boy.” A block behind the square, he suddenly stopped by a doorway. “My grandfather’s brother was shot on this spot by a man he had blackballed from a club. My great-grandparents, who were very devout, spent the rest of the night urging him to forgive the killer so that he would not die with the sin of hatred on his conscience. Meanwhile, he bled to death.” Following the 1979 revolution, the Club Social de Granada, the grandee bastion that had inspired the murder, became a workers club whose members would once have been barred even from using the sidewalk in front of the building. As we strolled through the past, the nightlife of contemporary Granada flowed around us—young, cheerful, and almost entirely pedestrian.

Among the elegant houses that we paused to admire was one bearing a plaque noting that giuseppe garibaldi, hero of two worlds had lived there in 1851. That the great Italian patriot who helped unify his country had passed through Nicaragua should come as no surprise. So many people did, from the English pirate Henry Morgan, who raided and sacked Granada in 1665, to Mark Twain, to the eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes, who befriended Somoza and lodged in the old Hotel Inter-Continental in Managua until dislodged by the earthquake. In fact, for much of human history Nicaragua has been a crossroads, not only because it sits between North and South America but also because, prior to the Transcontinental Railroad and the Panama Canal, it provided the most convenient route for getting from the Eastern Seaboard to California, or, as in Twain’s case when he came this way in 1866, vice versa. This was particularly important during the Gold Rush, when thousands of hopeful migrants made their way up the San Juan River from the Caribbean coast and across Lake Nicaragua. Three and a half hours in a horsedrawn carriage brought them to the Pacific Coast, where they re-embarked and sailed north to make their fortune, or not.

Not only an international crossroads, Nicaragua has served equally well as a hiding place. Henry Morgan had no need to go far to escape pursuit. He merely sailed a few miles across Lake Nicaragua to Las Isletas, the archipelago, lush with foliage, clustered near the shore. Once among the isles, he was as safely secluded as if he had fled a thousand miles.

Though I had left Granada unsacked just a few minutes before, I understood how Morgan probably felt as the Jicaro Island Ecolodge motor launch began threading its way through these same islands—a pleasurable sensation of escape to a hidden refuge. My first glimpse of the lodge only bolstered that feeling, given the artful manner in which the buildings have been blended into the mantle of shrubs and trees—towering ceiba, spiky elequeme, and of course jicaro. Each of the nine casitas offers a beguiling lake view, whether from bed or hammock. In keeping with the overall theme of natural harmony, all of the wood used for construction or for furniture came from trees downed by Hurricane Felix, which hit Nicaragua in 2007. Most of the wastewater is recycled to irrigate the trees and plants. “We put nothing back in the lake,” I was assured. Having also been assured that the lake’s few remaining freshwater sharks were miles away, I swam off the little beach to another, uninhabited island a few dozen yards away, and then returned for less strenuous immersion in the infinity pool. All that was lacking was someone behind the adjacent bar to pour me a drink—a minor flaw remedied before lunch, an event I looked to with eager anticipation, given the exemplary skills of the Jicaro chefs. While more-energetic fellow guests shopped in Granada or hiked amid the exotic flora on the slopes of nearby Mombacho Volcano, I took a kayak from the beach and glided deeper into the archipelago, with only a yellow-tailed chestnut bird for company.

As I crossed Lake Nicaragua a few days later, the perfectly symmetrical twin volcanoes of Concepción and Maderas rose from the island of Ometepe, an undeniably breathtaking vista that kicked Twain’s pen into lyrical overdrive: “They look so isolated from the world and its turmoil—so tranquil, so dreamy, so steeped in slumber and eternal repose.” He was wrong on the eternal repose, since the northernmost of the two, Concepción, erupted a few years after his visit and has continued to do so at regular intervals ever since. Next to the beach at Hotel Charco Verde, where I checked in, I took an early-morning swim in the still waters of the Green Lagoon, which confirmed the Twain verdict on tranquillity.

His presumption of isolation seemed reasonable enough, but pre-Columbian artifacts in the island’s delightful El Ceibo archaeological museum suggest that once upon a time Ometepe was an important destination, attracting travelers and pilgrims from all over Central America and beyond. Amid the local wares, beautifully produced over two millennia, are others brought from far away—a gold amulet from Colombia, ceramics from distant Peru and Mexico, a mysteriously intricate container of unknown purpose from El Salvador. Most strikingly, the bulk of the collection was dug up in the immediate vicinity of the museum and is on display because the landowners were interested enough to preserve the pieces rather than selling or tossing them aside. “If this is all from one farm,” declared Bismark Garcia, the agreeably passionate young museum guide, “imagine what else was on our island.” One of the display cases features artifacts from a period when power in island culture shifted to women—thus launching a Nicaraguan tradition, suggested Bismark, that continued in modern times with the election of a female president, Violeta Chamorro, in 1990, and the present incumbency of a female chief of police. (He didn’t mention Rosario.)

Later, as I strolled the slopes of Maderas, the island’s dormant volcano, I found more reminders that Ometepe had a vibrant history. Under trees festooned with Congo monkeys were clusters of rocks covered in flowing petroglyphs. Some were spirals or other abstract patterns; others revealed creatures from the world around me—a butterfly, a fish. Under my feet was a face, adapted by the artist from the natural contours of the rock. On Ometepe, magic is never far away.

Bismark suggested that the visitors from Peru had come to Nicaragua by water up the Pacific coast. These ancient travelers were probably less appreciative of the Pacific beaches than the young international set who flock to the busy beach town of San Juan del Sur for the superb surfing, not to mention party life. I was drawn to the coast not by the big waves but by the unspoiled coastline and the promise of an ocean rich in fish. Thus it was that I checked into Morgan’s Rock, an ecolodge on a grand scale half an hour north of town, surrounded by roughly 4,500 acres of forest. Guest bungalows are accessed via a suspension footbridge arcing through the treetops—slightly disconcerting on arrival in the pitch dark. My airy bungalow was the epitome of seaside comfort, especially given the relaxing rhythm of surf on the beach below. The sense of congenial exclusivity was only enhanced by the absence of other guests. (Nicaraguans were still recovering from the Easter Week holiday blowout.)

Heading north along the coast on a fishing boat rented for the day with Lloyd, the professional sport fisherman commanding our expedition, we passed beach after untouched beach. Rocky headlands bloomed with white sacuanjoche blossoms. Overhead, frigate birds wheeled and dived, along with flights of pelicans proceeding in neat formation. Gratifyingly regular tugs on the line signaled the arrival of delicately patterned Spanish mackerel and gleaming silver roosterfish. In the prow of the boat, one of the fishermen cleaned a mackerel and began chopping and dicing it along with green peppers, then squeezing limes, pausing to sharpen his knife, patiently chopping again, adding other ingredients and yet more lime juice before finally passing around the result: unbeatably fresh and delicious seviche.

Eventually, we arrived at a particular stretch of gleaming sand that is ground zero for what the Pellas family, the country’s richest, is betting will become the showcase for high-end Nicaraguan resort development. Guacalito de la Isla will feature beach houses (already in hot demand among affluent locals) along with a world-class golf course, hotel, spa, and beach club. Lloyd thought that this would be a tasteful contrast to San Juan del Sur. Despite having transited from French to Australian nationality—”I saw an ad that said, ‘Why not Australia?’ “—he retained some Gallic traits. “How shall I say this?” he murmured. “San Juan del Sur does not attract the cream of the cream of Americans.”

Continued (page 3 of 3)

Lloyd certainly knew how to attract the cream of sport fish, a skill he deploys around the world on behalf of luxury resorts. The next morning, we headed out into the Pacific to hunt for bigger game. Twenty miles from shore, a ferocious jerk on one of the lines initiated my long struggle with a fifty-pound sailfish that slipped away just as it was being gaffed into the boat. I had better luck with a twentypound mahimahi. We hauled it aboard before calling it a day and battled home through breakers whipped by a stiffening thirty-five-knot wind. My fish, delectable above all others when grilled fresh, fed not only me but everyone else at the hotel that day, which classified me as an über-ecotourist, sustaining as well as sustainable.

For deeper immersion into Nicaragua’s natural environment, however, I had to drive four hours northwest, back past Granada and Managua, and up another of Nicaragua’s beautifully graded roads to Matagalpa and its green mountains and long valleys. Much of this peaceful area, a mine-strewn battlefield during the era of U.S.–sponsored contra invasion in the 1980s, is coffee country, traditionally poor but currently prospering owing to sky-high global coffee prices.

More than a century ago, the Nicaraguan government solicited German immigrants to come and grow coffee here, among them the ancestors of Eddy and Mausi Kuhl, whose plantation and lodge at Selva Negra gives new meaning to organic and sustainable. Used plastic water bottles, for example, scourge of the modern world, are here treasured as a means of eliminating coffeeborer bugs, scourge of the coffee farmer, through a simple process of attracting them with a solution of coffee and alcohol in an eyedropper attached to the top of a bottle. Drunk, they fall into the water at the bottom of the bottle and drown. “We kill millions per year,” exclaimed Mausi triumphantly as she patrolled the property.

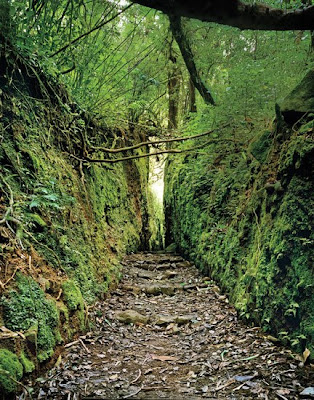

There seemed no limit to the delightful ingenuity on display around me; residue from processing the coffee beans ends up as methane gas in the kitchen stoves; a failed effort to grow giant lemons has evolved into a lemon-tinged coffee, with a chocolate variety that may soon follow; ground-up hedge clippings become natural pesticides. Overwhelmed by the degree to which all biological activities—animal, vegetable, and human—are used and reused here, I suggested to Mausi that the function of us guests in her hotel was merely to play a role in the fertilizer production chain. “Maybe that’s true,” she said with a laugh. Above the busy plantation, five hundred acres of triple-canopy cloud forest rose steeply to the ridgeline, an Eden of towering ficus trees, orchids, Congo monkeys, brilliantly plumaged quetzals, toucans, and more.

Mausi had warned me that two steps off the trail and I would be lost. I found that easy to believe, but then, as Henry Morgan realized long ago, you don’t have to go very far in Nicaragua to escape from the world.

Among the more exotic examples of others who have taken advantage of this is Alessio Casimirri, once a member of the 1970s-era Italian terrorist Red Brigades. High on the Italian wanted list for his alleged role in the kidnapping of former prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978, he made his way to Nicaragua and garnered security from extradition by marrying a Nicaraguan. Today, he presides over the restaurant La Cueva del Buzo, a mecca for Managuan seafood and pasta aficionados, where the menu features pictures of Alessio in diving gear, holding an impressive-sized catch. The Italian ambassador has purportedly lobbied fellow diplomats to boycott the place, but since I am not a diplomat, when I returned to Managua the night before catching my flight home, I couldn’t resist trying the restaurant’s acclaimed cuisine. Indeed, I saw diplomatic plates on several of the vehicles parked outside. Inside, expensive cigar smoke wafted from the Swiss ambassador’s adjacent table. Seated in the corner was the proprietor’s mother, who showed me her bragging wall: pictures of her late husband, who had served as Vatican press secretary, and of her father, former chief of protocol at the Vatican, in the company of popes Pius XII, John XXIII, and Paul VI. One picture featured little Alessio playing in the Vatican gardens.

The slightly surreal context of my dinner was only augmented by the discussion at my table between my friends Camilo Belli and Arturo Cruz. Arturo has had a peripatetic political career, ranging from heavy involvement with the U.S.-backed contras in the 1980s to a more recent spell as Daniel Ortega’s ambassador in Washington, while Camilo retains the principles with which he was raised in a revolutionary household. Yet in a polite but intense discussion over pasta e olio, fillet Alessio (fish in orange sauce), and chocolate mousse, Arturo, the former contra, argued the case for Ortega’s candidacy in the upcoming election, citing the president’s popular support and the nonviability of any opposition candidates. He was ardently rebutted by Camilo, who justified his active support for a highly conservative candidate on the grounds that Ortega is mangling the constitution, traducing the judicial system, stifling the independent media, and generally leading the country in a disastrous direction. A flat-screen monitor on the wall flickered with a loop of Alessio’s spearfishing home videos. No one won the argument, and finally we all went our separate ways in the peaceful, balmy night, paradoxes intact.

World Savers: Among the places Andrew Cockburn stayed at to report this story is Lake Nicaragua’s Jicaro Island Ecolodge, operated by 2010 World Savers Award winner Cayuga Sustainable Hospitality and its only property outside Costa Rica. (In Costa Rica, the company manages Lapa Rios and Finca Rosa Blanca, among others.) Cayuga has vast ambitions to redefine upscale hospitality—aggressively conserving energy and water, working with suppliers to reduce packaging, supporting local farmers, building recycling centers. One ongoing challenge: eliminating plastic water bottles. “Why can’t every company do this?” asks firebrand CEO Hans Pfister. For this year’s World Savers Awards, click here.

Photographs by Trujillo Paumier

7